NFHS Medical Release Form for Skin Lesions

Click Here to Download

Cold Sores (HSV-1)

Neal knew something weird was going on. A few days before, his lip started tingling and felt a little numb. He didn’t pay much attention to it then, but now there was a certain throbbing something on his lip and it wasn’t pretty. At first Neal thought it was a zit because it was red and tender, but then it blistered and opened up. Neal had a cold sore.

Maybe you’ve heard of a fever blister — a cold sore is the same thing. They’re pretty common and lots of people get them. So what exactly are cold sores and what causes them?

What’s a Cold Sore?

Cold sores, which are small and somewhat painful blisters that usually show up on or around a person’s lips, are caused by the herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1). But they don’t just show up on the lips. They can sometimes be inside the mouth, on the face, or even inside or on the nose. These places are the most common, but sores can appear anywhere on the body, including the genital area.

Genital herpes isn’t typically caused by HSV-1; it’s caused by another type of the herpes simplex virus called herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) and is spread by sexual contact. But even though HSV-1 typically causes sores around the mouth and HSV-2 causes genital sores, these viruses can cause sores in either place.

What Causes a Cold Sore?

HSV-1 is very common — if you have it, chances are you picked it up when you were a kid. Most people who are infected with the herpes simplex virus got it during their preschool years, most likely from close contact with someone who has it or getting kissed by an adult with the virus.

Although a person who has HSV-1 doesn’t always have sores, the virus stays in the body and there’s no permanent cure.

When someone gets infected with HSV-1, the virus makes its way through the skin and into a group of nerve cells called a ganglion (pronounced: gang-glee-in). The virus moves in here, takes a long snooze, and every now and then decides to wake up and cause a cold sore. But not everyone who gets the herpes simplex virus develops cold sores. In some people, the virus stays dormant (asleep) permanently.

What causes the virus to “wake up” or reactivate? The truth is, no one knows for sure. A person doesn’t necessarily have to have a cold to get a cold sore — they can be brought on by other infections, fever, stress, sunlight, cold weather, hormone changes in menstruation or pregnancy, tooth extractions, and certain foods and drugs. In a lot of people, the cause is unpredictable.

Here’s how a cold sore develops:

- The herpes simplex virus-1, which has been lying dormant in the body, reactivates or “wakes up.”

- The virus travels toward the area where the cold sore decides to show up (like a person’s lip) via the nerve endings.

- The area below the skin’s surface, where the cold sore is going to appear, starts to tingle, itch, or burn.

- A red bump appears in the area about a day or so after the tingling.

- The bump blisters and turns into a cold sore.

- After a few days, the cold sore dries up and a yellow crust appears in its place.

- The scab-like yellow crust falls off and leaves behind a pinkish area where it once was.

- The redness fades away as the body heals and sends the herpes simplex virus back to “sleep.”

How Do Cold Sores Spread?

Cold sores are really contagious. If you have a cold sore, it’s very easy to infect another person with HSV-1. The virus spreads through direct contact — through skin contact or contact with oral or genital secretions (like through kissing). Although the virus is most contagious when a sore is present, it can still be passed on even if you can’t see a sore. HSV-1 can also be spread by sharing a cup or eating utensils with someone who has it.

In addition, if you or your partner gets cold sores on the mouth, the herpes simplex virus-1 can be transmitted during oral sex and cause herpes in the genital area.

Herpes simplex virus-1 also can spread if a person touches the cold sore and then touches a mucous membrane or an area of the skin with a cut on it. Mucous membranes are the moist, protective linings made of tissue that are found in certain areas of your body like your nose, eyes, mouth, and vagina. So it’s best to not mess with a cold sore — don’t pick, pinch, or squeeze it.

Actually, it’s a good idea to not even touch active cold sores. If you do touch an active cold sore, don’t touch other parts of your body. Be especially careful about touching your eyes — if it gets into the eyes, HSV-1 can cause a lot of damage. Wash your hands as soon as possible. In fact, if you have a cold sore or you’re around someone with a cold sore, try to wash your hands frequently.

If they aren’t taken care of properly, cold sores can develop into bacterial skin infections. And they can actually be dangerous for people whose immune systems are weakened (such as infants and people who have cancer or HIV/AIDS) as well as those with eczema. For people with any of these conditions, an infection triggered by a cold sore can actually be life threatening.

How Are Cold Sores Diagnosed and Treated?

Cold sores normally go away on their own within 7 to 10 days. And although no medications can make the infection go away, prescription drugs and creams are available that can shorten the length of the outbreak and make the cold sore less painful.

If you have a cold sore, it’s important to see your doctor if:

- you have another health condition that has weakened your immune system

- the sores don’t heal by themselves within 7 to 10 days

- you get cold sores frequently

- you have signs of a bacterial infection, such as fever, pus, or spreading redness

To make yourself more comfortable when you have cold sores, you can apply ice or anything cool to the area. You also can take an over-the-counter pain reliever, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

Impetigo

Impetigo, a contagious skin infection that usually produces blisters or sores on the face, neck, hands, and diaper area is one of the most common skin infections among kids.

It is generally caused by one of two bacteria: staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococcus. Impetigo usually affects preschool and school-age children. A child may be more likely to develop impetigo if the skin has already been irritated by other skin problems, such as eczema, poison ivy, and insect bites.

Good hygiene can help prevent impetigo, which often develops when there is a sore or a rash that has been scratched repetitively (for example, poison ivy can get infected and turn into impetigo). Impetigo is typically treated with either an antibiotic cream or medication taken by mouth.

Signs and Symptoms

Impetigo may affect skin anywhere on the body but commonly occurs around the nose and mouth, hands, and forearms and diaper area in young children.

There are two types of impetigo: bullous impetigo (large blisters) and non-bullous impetigo (crusted) impetigo. The non-bullous or crusted form is most common. This is usually caused by staphylococcus aureus but can also be caused by infection with group A streptococcus. Non-bullous begins as tiny blisters. These blisters eventually burst and leave small wet patches of red skin that may weep fluid. Gradually, a tan or yellowish-brown crust covers the affected area, making it look like it has been coated with honey or brown sugar.

Bullous impetigo is nearly always caused by staphylococcus aureus, which triggers larger fluid-containing blisters that appear clear, then cloudy. These blisters are more likely to stay intact longer on the skin without bursting.

Contagiousness

Impetigo may itch and kids can spread the infection by scratching it and then touching other parts of the body.

Impetigo is contagious and can spread to anyone who comes into contact with infected skin or other items, such as clothing, towels, and bed linens, that have been touched by infected skin.

Treatment

When it just affects a small area of the skin, impetigo can usually be treated with antibiotic ointment. But if the infection has spread to other areas of the body, or the ointment isn’t working, the doctor may prescribe an antibiotic pill or liquid.

Once antibiotic treatment begins, healing should start within a few days. It’s important to make sure that your child takes the medication as the doctor has prescribed. If that doesn’t happen, a deeper and more serious skin infection could develop.

While the infection is healing, gently wash the areas of infected skin with clean gauze and antiseptic soap every day. Soak any areas of crusted skin in warm soapy water to help remove the layers of crust (it is not necessary to completely remove all of it).

To keep your child from spreading impetigo to other parts of the body, the doctor or nurse will probably recommend covering infected areas of skin with gauze and tape or a loose plastic bandage. Keep your child’s fingernails short and clean.

Prevention

Good hygiene practices, such as regular hand washing, can help prevent impetigo. Have kids use soap and water to clean their skin and be sure they take baths or showers regularly. Pay special attention to areas of the skin that have been injured, such as cuts, scrapes, bug bites, areas of eczema, and rashes such as poison ivy. Keep these areas clean and covered.

Anyone in your family with impetigo should keep fingernails cut short and the impetigo sores covered with gauze and tape.

Prevent impetigo infection from spreading among family members by using antibacterial soap and making sure that each family member uses a separate towel. If necessary, substitute paper towels for cloth ones until the impetigo is gone. Separate the infected person’s bed linens, towels, and clothing from those of other family members, and wash these items in hot water.

When to Call the Doctor

Call the doctor if your child has signs of impetigo, especially if he or she has been exposed to a family member or classmate with the infection. If your child is already being treated for impetigo, keep an eye on the sores and call the doctor if the skin doesn’t begin to heal after 3 days of treatment or if a fever develops. If the area around the rash becomes red, warm, or tender to the touch, notify the doctor as soon as possible

Tinea (Ringworm)

Although the words ringworm, jock itch, and athlete’s foot may sound funny, if you’re a teen with one of these skin infections, you’re probably not laughing. If you’ve ever had one, you know that any of these infections can produce some pretty unpleasant symptoms. The good news is that tinea, the name for this category of common skin infections, is generally easy to treat. Read on to learn more about ringworm.

The Basics on Tinea Infections

Tinea (pronounced: tih-nee-uh) is the medical name for a group of related skin infections, including athlete’s foot, jock itch, and ringworm. These infections are caused by several types of mold-like fungi called dermatophytes (pronounced: der-mah-tuh-fites) that live on the dead tissues of the skin, hair, and nails.

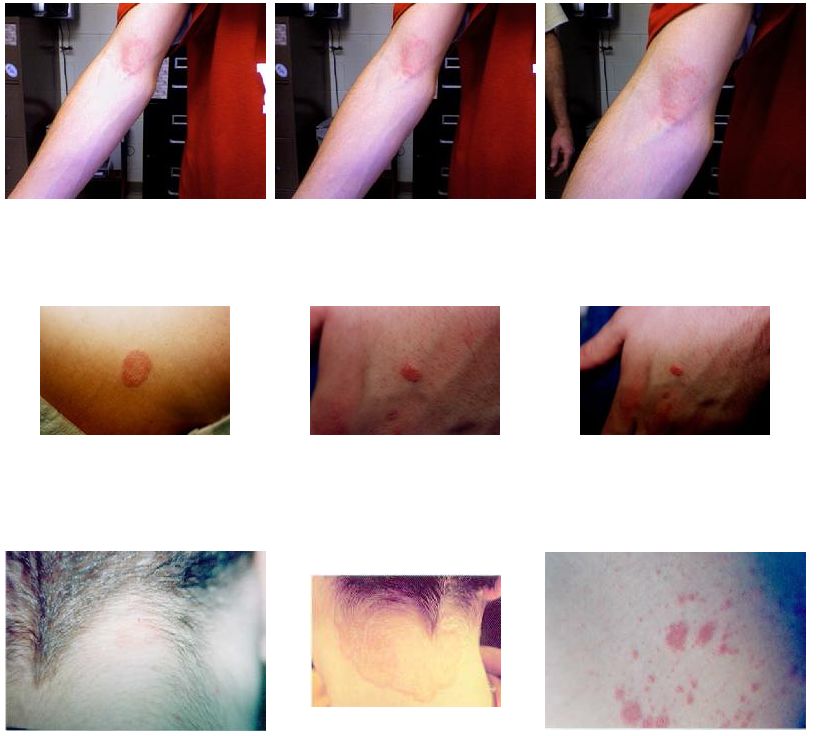

What Is Ringworm?

Ringworm, which isn’t a worm at all, can affect not only the skin, but also the nails and scalp.

Ringworm of the skin starts as a red, scaly patch or bump. Ringworm tends to be very itchy and uncomfortable. Over time, it may begin to look like a ring or a series of rings with raised, bumpy, scaly borders (the center is often clear). This ring pattern gave ringworm its name, but not every person who’s infected develops the rings.

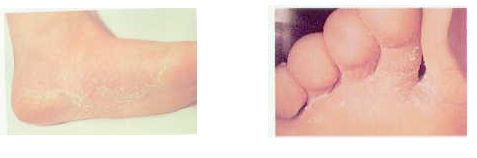

When ringworm affects the feet it’s known as athlete’s foot, and the rash, which is usually between a person’s toes, appears patchy. In fact, the rashes a person gets with athlete’s foot and jock itch may not look like rings at all — they may be red, scaly patches.

Ringworm of the scalp may start as a small sore that resembles a pimple before becoming patchy, flaky, or scaly. It may cause some hair to fall out or break into stubbles. It can also cause the place where the infection is to become swollen, tender, and red.

Ringworm of the nails may affect one or more nails on a person’s hands or feet. The nails may become thick, white or yellowish, and brittle. Ringworm of the nails is not too common before puberty, though.

Can I Prevent Ringworm?

The most common sources of the fungi that cause tinea infections are other people. Ringworm is contagious and is easily spread from one person to another, so avoid touching an infected area on another person. It’s also possible to become infected from contact with animals, like cats and dogs.

It can be difficult to avoid ringworm because the dermatophyte fungi are very common. To protect yourself against infection, it can help to wear flip-flops on your feet in the locker room shower or at the pool, and to wash sports clothing regularly. Because fungi are on your skin, it’s important to shower after contact sports and to wash your hands often, especially after touching pets.

If you discover a red, patchy, itchy area that you think may be ringworm, call your doctor.

How Is Ringworm Treated?

Fortunately, ringworm is fairly easy to diagnose and treat. Doctors usually can diagnose ringworm based on how it looks, but sometimes will scrape off a small sample of the flaky infected skin to test for fungus.

If you do have ringworm, your doctor will recommend an antifungal medication. A topical ointment or cream usually takes care of skin infections, but ringworm of the scalp or nails requires oral antifungal medication. Your doctor will decide which treatment is best for you.

MRSA- What Is MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Staphylococcus aureus is a type of bacteria with lots of different strains.

Many strains of staph bacteria are quite common. Most people have staph bacteria living on their skin or in their noses without causing any problems. If staph bacteria get into a person’s body through a cut, scrape, or rash, they can cause minor skin infections. Most of these heal on their own if a person keeps the wound clean and bandaged. Sometimes doctors prescribe antibiotics to treat more stubborn staph infections.

What makes the MRSA different from other staph infections is that it has built up an immunity to the antibiotics doctors usually use to treat staph infections. (Methicillin is a type of antibiotic, which is why the strain is called “methicillin-resistant.”)

MRSA can also cause more serious infections, such as pneumonia, although this is rare.

How Do People Get It?

MRSA is making headlines, but it’s not a new infection. The first case was reported in 1968. In the past, MRSA usually affected people with weakened immune systems, such as those living in long-term care facilities like nursing homes.

But now some otherwise healthy people who are not considered at risk for MRSA are getting the infection. Doctors call this type of infection community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) because it affects people who spend time together in groups, such as schools, college dorms, or military barracks.

When lots of people come together and are likely to touch the same surfaces, have skin-to-skin contact, or share equipment that has not been cleaned, an infection can spread faster than it would otherwise. That’s why recent MRSA infections involved athletes in gyms and locker rooms. If the MRSA bacteria get onto a kneepad, for example, and someone with a skinned knee wears the pad without cleaning it, that person’s risk of infection is higher.

How Can I Protect Myself?

MRSA may sound scary because it is resistant to some antibiotics. But it’s actually easy to prevent MRSA from spreading by practicing simple cleanliness.

Protect yourself by taking these steps:

- Wash your hands often using plain soap and water for at least 15 seconds each time. You might also want to carry alcohol-based instant hand sanitizers or wipes in your bag for times when you can’t wash your hands.

- If you have a cut or broken skin, keep it clean and covered with a bandage.

- Don’t share razors, towels, uniforms, or other items that come into contact with bare skin.

- Clean shared sports equipment with antiseptic solution before each use or use a barrier (clothing or a towel) between your skin and the equipment.

Even in the rare event that someone in your school becomes infected with MRSA, you can protect yourself by washing your hands, wiping any surfaces before they come into contact with your skin, and keeping any cuts covered.

How Is MRSA Treated?

MRSA infections can require different medications and approaches to treatment than other staph infections. For example, if a person has a skin abscess caused by MRSA, the doctor is more likely to have to drain the pus from the abscess in order to clear the infection.

In addition to draining the area, doctors may prescribe antibiotics for some people with MRSA infections. In a few cases, MRSA can spread throughout the body and cause problems like blood and joint infections — although complications like these are very rare in healthy people.

People with infections can also help prevent future bacteria from becoming resistant to antibiotics by taking the antibiotics that have been prescribed for them in the full amount until the prescription is finished (unless a doctor tells them it’s OK to stop early). Germs that are allowed to hang around after incomplete treatment of an infection are more likely to become resistant to antibiotics.

When Should I Call the Doctor?

Call the doctor if:

- You have an area of skin that is red, painful, swollen, and/or filled with pus.

- You have an area of swollen, painful skin and also feel feverish or sick.

- Skin infections seem to be passing from one family member to another (or among students in your school) or if two or more family members have skin infections at the same time.

Serious cases of MRSA are still rare. By taking these easy prevention steps, you can help keep it that way!

Precautions Against MRSA Skin Infections

What is MRSA?

While originally found primarily in hospitals, a drug-resistant bacteria known as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is increasingly occurring in schools. In fact, according to the August edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, MRSA is among the most common causes of skin and soft-tissue infections treated in emergency rooms at eleven hospitals across the United States.

Hospital-associated MRSA has been known since the 1960s, but community-associated strains have emerged only in recent years. Children are especially susceptible to MRSA. It is estimated that Staphylococcus aureus bacteria are carried by 30% of the population, and is easily passed from one person to another. This doesn’t necessarily cause an infection unless there is a break in the skin, like from an insect bite or scratch.

How Can We Prevent MRSA Infections?

As with most things, prevention is important to avoid these infections. Understanding that “staph” and MRSA are usually spread from having close contact with infected people, there are precautions that can help you avoid these infections. In addition to direct physical contact, MRSA may also be spread by indirect contact by touching objects (towels, sheets, wound dressings, clothes, workout areas, and sports equipment) contaminated by the infected skin of a person with MRSA or staph bacteria.

To avoid staph and MRSA, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that everyone practice good hygiene, as follows:

· Keep your hands clean by washing thoroughly with soap and water.

· Clean thoroughly after athletic workouts and contact with other players.

· Utilize alcohol-based hand sanitizers when soap and water are unavailable.

· Launder athletic uniforms and other athletic clothing in hot water and dry them in a hot dryer.

· Sanitize athletic equipment after use to avoid transmission of bacteria.

· If you have an open wound, be sure to clean it well, and keep it covered with a bandage that attaches to the skin on all sides.

· Never share or borrow towels, razors, soap, or any other personal items.

Cherry Hill’s Proactive Approach

· All school nurses have been apprised of the signs and symptoms of the infection. They are communicating with the custodians assigned to each building to ensure that “high-risk” areas are targeted and that the overall cleanliness of the buildings is maintained.

· Gym areas, locker rooms, weight rooms, wrestling rooms, aerobic rooms, athletic areas, all-purpose rooms, and bathrooms are targeted as “high risk areas.” Appropriate cleaning techniques are in place using hospital-grade disinfectant, which kills bacteria, fungi, and viruses – including MRSA.

· Athletic trainers are knowledgeable in both recognition and referral of students with any skin infection, and coaches have been instructed by the trainers in such areas.

· Education is the key, as well as hand washing and good hygiene. Basic principles of “No Sharing” of personal objects will greatly reduce the spread of this and any infection.

· Nurses and trainers are the key people in each building and all questions and concerns should be directed to them.

We must all work together to promote health and wellness in our schools.

See a physician immediately upon observing any new skin lesion; if your physician suspects MRSA, please notify the school nurse as soon as possible so that we can continue to be proactive in preventing the spread of the infection. If your student has a confirmed MRSA diagnosis, we will take the steps necessary to notify appropriate county health officials.

Please call your family physician if you have any additional questions about MRSA. You can also visit the district website (www.chclc.org) or following websites for updates and more information:

http://www.cdc.gov/Features/MRSAinSchools/

http://nj.gov/health/cd/mrsa/index.shtml

Athletes Foot